Why I Wrote The Documentation

Some books arrive fully formed. This one came in pieces — loose pages scattered across years, scenes that didn't yet know they belonged together, a story that kept insisting I wasn't done with it.

I've spent over a decade as a subject matter expert in family safety, sitting with survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault, and human trafficking. I've also sat across from perpetrators. You learn things in that work that don't leave you — how trauma lives in the body, how silence becomes its own kind of violence. How some people disappear, and the world barely notices.

The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Crisis

The Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women crisis isn't new. It's generations deep. Women vanish from reservations, from border towns, from places most Americans will never visit, and their names don't trend, their faces don't make the evening news. They become statistics, if they're counted at all.

I knew I wanted to write about this. I didn't know how.

Then There Are the Petroglyphs

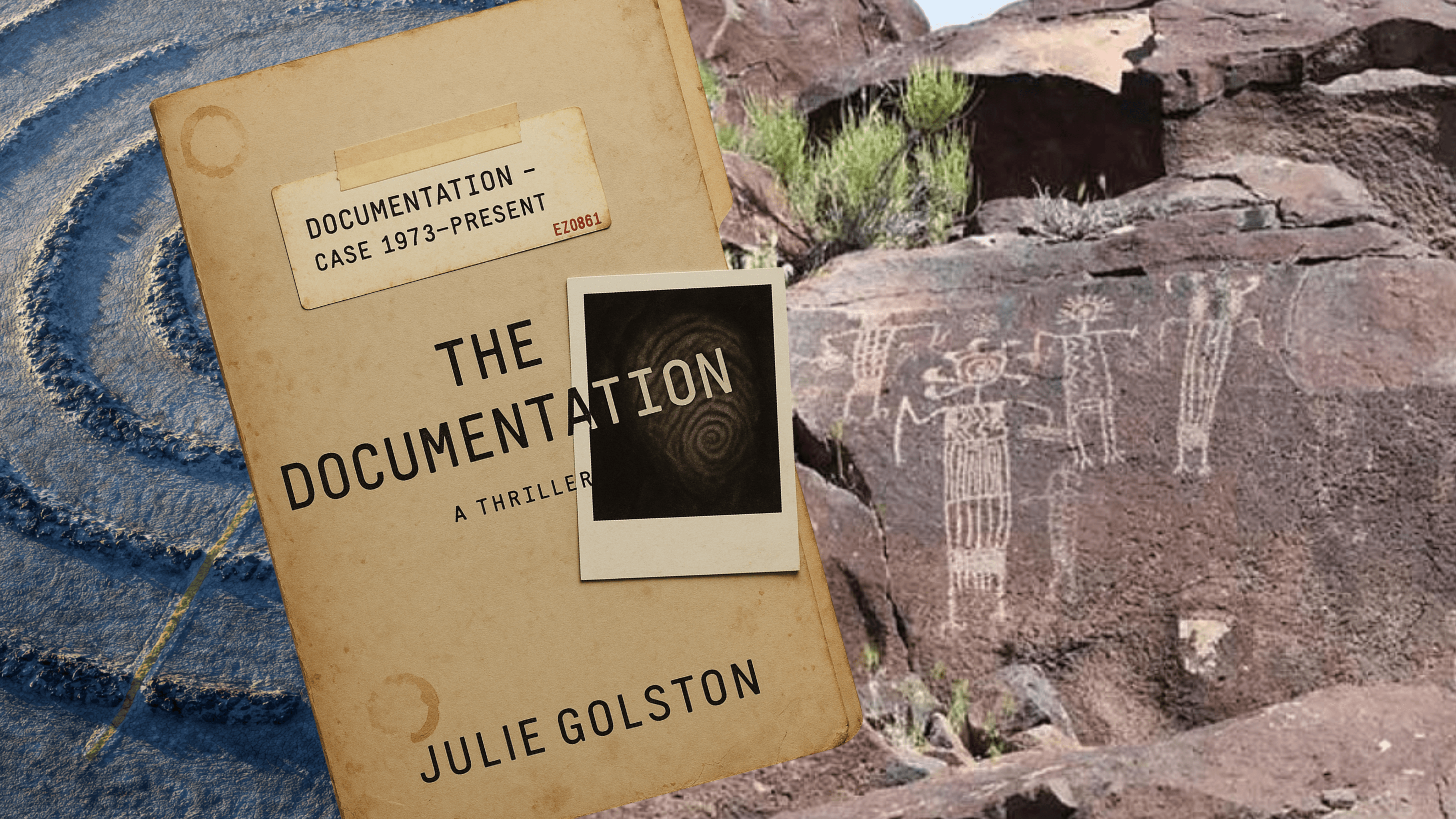

I live in the Mojave Desert, near the Coso Range — home to one of the largest concentrations of rock art in North America. Thousands of images carved into basalt by people who lived here long before anyone called it California. I think about them often. What compels someone to carve into stone? It's a way of saying: I was here. Remember me. Don't let me disappear.

That collision — ancient voices etched into rock, and modern women whose disappearances leave no mark at all — is where this book was born.

Why a Thriller?

The Documentation is about FBI Agent Sarah Holt and a four-year-old girl who carries the voices of murdered Indigenous women. It's my first thriller, and I chose the genre deliberately. I wanted readers to feel the urgency, the stakes, the way time runs out for women no one is looking for. Thriller lets you do that. It puts you in the body of someone racing against something, and it doesn't let you look away.

I won't pretend this book was easy to write. It asked things of me. It made me sit with what I know professionally and what I feel personally and find a story that could hold both.

The Story Is Complete

And now, after all the loose pages, all the years — the story is complete. The Documentation is the first book in the Spiral Trilogy, and its sequel, The Archive, is already taking shape.

I hope it stays with you. I hope it makes you remember names. I hope, when you experience this story, you understand why a four-year-old had to be the one to carry those voices.

Some people carve into stone. Some write books. Either way, we're saying the same thing:

Don't let them disappear.